The Doctrine of Adoption: Revisited

What is the Doctrine of Adoption?

Systematic theology can be a wonderful thing. It can also cause a lot of problems. Perhaps the greatest benefit of systematic theology is that it attempts to articulate the teaching of Scripture in a clear, digestible, cohesive way. The greatest weakness is that these theological systems can obscure the full teaching of Scripture if the system is off. In the case of the biblical doctrine of adoption, it seems the major theological systems have all failed to faithfully articulate the full biblical teaching. At the very least, they have produced a commonly held misperception about adoption that is only partially true.

What is the doctrine of adoption? The doctrine of adoption refers to the aspect of salvation in Christian theology in which the believer is adopted into the family of God and considered as a son or daughter of God. As sons and/or daughters of God, believers are granted an everlasting inheritance in the Kingdom of God. The doctrine of adoption helps to illustrate the amazing and lavish grace of God in Christ because it shows the extent of God’s redemptive purpose. It is not enough for God to simply forgive rebellious criminals in Christ. Instead, God goes even further to adopt the redeemed into His family as His heirs. All of this is the “what” of the doctrine of adoption. Most, if not all, major systems of theology agree on these general truths regarding adoption. However, the major systems of theology incorrectly assert that adoption happens entirely at (or near) the moment of salvation when a person repents and believes in Jesus Christ. When the full biblical teaching on adoption is considered, it becomes clear that there is a future aspect of adoption which Christians are exhorted to eagerly look forward to at the end of their salvation process.

Let’s dig deeper into this important and often misunderstood doctrine. The truth is more glorious than most people realize.

What Does The Bible Say About Adoption?

In order to fully understand the imagery of children of God we must briefly dig into the doctrine of adoption. As we look to the Scriptures, it is important that we pause what we think we know so we don’t miss what the text plainly says. Our theological assumptions can cause major problems and create massive blind spots.

With many doctrines in Scripture, there are a huge number of passages that must be considered. We are fortunate in the case of adoption that this is not the case. The word translated as adoption (GK: huiothesia) only occurs in the New Testament five times. The Apostle Paul is the only biblical author to use this terminology. This makes it relatively easy to do an exhaustive study of the passages and then to systematize those teachings on the doctrine of adoption.

The terminology of being a child of God is much more widely used. However, it is the Apostle Paul who, by and large, describes the glorious aspect of adoption in the process of our salvation. Other Greek words can and should be included in a more in-depth study. However, space will not allow us to delve deeper into an examination of all 377 occurrences of huios (“son/sons”), the 99 occurrences of teknon (“child/children”), or the 343 occurrences of adelphos (“brothers/brethren”).

For those who conduct these fuller studies, the results will support the conclusions drawn in this article.

Adoption Meaning

The Greek word translated as “adoption” in the New Testament is huiothesia. This compound word has huios as the first part. Huios is a Greek word most commonly translated as “son.” The term huios often (but not always) connotes not just a son, but a mature son. It is the only Greek word ever used of Jesus as the “Son of God.”

In John 1:12, a slightly less common word is used. It is also translated as “children.” Here, the word is not huios but rather teknon. Teknon can denote either a male or female child (that is, a son or a daughter). It can also denote a child that has not yet reached maturity. It is commonly used of younger children.

The process of adoption speaks of a legal process by which a child is brought to full maturity as an heir.

While this may not be the immediate thought of most who hear the term “adoption,” if we’ll think about it for a moment, none of this should really be that controversial. Think of our own society and laws. Even biological children cannot inherit their natural parents’ estate, by law, until they reach a legal age of maturity. Until maturation, the estate may be held in trust to be transferred once maturity is reached. In the same way, adoption is a legal process of making someone a full child and heir of another. While adoption can (and often does) happen at a young age, there is still a significant shift that occurs when a child (whether natural-born or adopted) reaches the age of maturity. It is then, and only then, that they become a full heir.

The Firstborn & Co-Heirs

Jesus is the “firstborn” of the house and kingdom of God (check out our series of articles on The Kingdom of God for a much more in-depth look at this major doctrine in Scripture). The word “firstborn” appears 141 times in the Bible, with only eight of these in the New Testament. Seven of the eight New Testament references refer to Jesus. The only other reference is in Hebrews 11:28, which speaks of the death of the firstborn in every house during the Passover.

Romans 8:29 (NASB)

For those whom He foreknew, He also predestined to become conformed to the image of His Son, so that He would be the firstborn among many brethren [GK: adelphos].Colossians 1:15, 18 (NASB)

He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation. … He is also head of the body, the church; and He is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead, so that He Himself will come to have first place in everything.

While some groups attempt to twist this teaching and diminish the divinity and eternality of Christ, the emphasis in the New Testament usage is that the “firstborn” is preeminent in the house as the primary heir. While it is true that the term “firstborn” is often speaking of birth order throughout the Old Testament, it is also used in the Old Testament to speak of a position of preeminence regardless of birth order. This fact can be proven easily by seeing how David is referred to as “the firstborn” even though he had seven older brothers (see Psalm 89:20–29 and 1 Samuel 16:6–11; 17:12–15).

“I also shall make him My firstborn,

The highest of the kings of the earth.”

“David was the youngest.”

God states His purpose in salvation: conforming believers into the image and likeness of Christ, so that Christ would be preeminent amongst a great multitude of believers from every tongue, tribe, nation, and people. How glorious that our salvation includes becoming joint heirs with Christ in His everlasting kingdom as members of the royal family of God!

Romans 8:16–17 (NASB)

The Spirit Himself testifies with our spirit that we are children of God, and if children, heirs also, heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ, if indeed we suffer with Him so that we may also be glorified with Him.

When Does Adoption Occur?

Although it can be difficult to find agreement between differing theological camps — for example, Calvinists and Arminians — we find that virtually all agree that adoption occurs at, or near, the moment of conversion.

The disagreement between these camps is more about logical order, not chronological order. Put another way, it is almost universally agreed that when the gospel is preached and a sinner responds in faith that the elements of calling, regeneration, faith, repentance, justification, and adoption all take place in some order in that moment. The argument is over the ordering of these events, even though the timing is confined to the same instant. While these events must happen in some logical order, they are not separated by enough time to warrant discussing their chronological order since, for all intents and purposes, they happen instantaneously and simultaneously.

Below is a comparison (from Wikipedia) of some of the major systems of theology. Notice, the ones that articulate adoption have it occurring at the moment of conversion in the midst of calling, regeneration, faith, repentance, and justification. While those other elements are ordered differently, depending on the system, adoption always finds itself at the end of the conversion event.

In these systems:

Everything above the top red line happened before the life of the individual.

Everything between the red lines is during the life of the believer.

Everything below the bottom red line happens after the resurrection/rapture.

The major systems teach that the elements of (external) calling, regeneration, faith, repentance, justification, and adoption (in whatever order) are assumed to all happen during the event or moment commonly referred to as “conversion.” When someone hears the gospel (“calling”) and turns to Jesus in faith (“repentance, faith, and regeneration” in some order), God declares them innocent of sin (“justification”) and adopts them into His family (“adoption”). From this point on, the process of sanctification begins and continues until glorification.

However, does the Bible actually agree with these major systems? As we examine the only five passages that speak of adoption, we can draw conclusions based on the entire teaching of the Bible on this topic. We will see that the Bible clearly teaches something about the timing of adoption that throws a wrench into the ordering of these events in all of these major theological systems.

Adoption in Romans

Of the five occurrences of adoption in the New Testament, three are in Romans. The first two are found in Romans 8. This passage is critical for understanding the rest of Paul’s teaching on this doctrine. The remaining passages do not contradict this passage, rather they are in full agreement with it.

Romans 8:14–25 (NASB)

For all who are being led by the Spirit of God, these are sons [GK: huios] of God. For you have not received a spirit of slavery leading to fear again, but you have received a spirit of adoption as sons [GK: huiothesia] by which we cry out, “Abba! Father!” The Spirit Himself testifies with our spirit that we are children [GK: teknon] of God, and if children [GK: teknon], heirs also, heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ, if indeed we suffer with Him so that we may also be glorified with Him.For I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory that is to be revealed to us. For the anxious longing of the creation waits eagerly for the revealing of the sons [GK: huios] of God. For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of Him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself also will be set free from its slavery to corruption into the freedom of the glory of the children [GK: teknon] of God. For we know that the whole creation groans and suffers the pains of childbirth together until now. And not only this, but also we ourselves, having the first fruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, waiting eagerly for our adoption as sons [GK: huiothesia], the redemption of our body. For in hope we have been saved, but hope that is seen is not hope; for who hopes for what he already sees? But if we hope for what we do not see, with perseverance we wait eagerly for it.

In this passage, we are immediately confronted with the already / not yet paradigm.

In verse 14, Paul plainly states that those who are led by the Spirit are sons of God. This is a present-tense reality for all who are being led by the Spirit. Paul then states that these have received a spirit of adoption as sons. Here we must be careful to see what the text does and does not say. It does not say “you were adopted” but rather that “you have received a spirit of adoption.” This spirit of adoption causes us to cry out in our own hearts to our Father. This agrees with the testimony of the Holy Spirit that we are children of God and fellow heirs with Christ.

However, Paul continues his discussion about the glory to come in the future for believers. This present-tense possession gives the children of God strength to endure through our present suffering as we look forward to our future glorification with Christ. Most of this is straight-forward in the main theological camps. However, Paul makes an important statement in verses 23–25 that can be easily missed.

And not only this, but also we ourselves, having the first fruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, waiting eagerly for our adoption as sons, the redemption of our body. For in hope we have been saved, but hope that is seen is not hope; for who hopes for what he already sees? But if we hope for what we do not see, with perseverance we wait eagerly for it.

Paul states explicitly that we are currently waiting for our adoption as sons, the redemption of our body. The next statement he makes speaks of our hope regarding this fact, since it is not something we currently possess. It is something we are waiting eagerly for. That is, no one hopes or waits for what they already possess.

Is this a contradiction? No!

We’ve received a spirit of adoption. We eagerly await the consummation of this adoption. If we look again at the ordo salutis chart, all the major theological systems look forward to the future redemption of our body. However, the way Paul describes adoption is what most theologians refer to as glorification, which is the last step in our salvation process.

While this view may not be popularly held, it is undeniable that Paul speaks of our adoption as something Christians (and really all of creation) is eagerly awaiting. It is yet to come. This will help us to correctly understand the remaining discussion of adoption written by Paul.

Adoption in Romans, Part 2

Paul discusses adoption again in the next chapter of Romans.

Romans 9:1–5 (NASB)

I am telling the truth in Christ, I am not lying, my conscience testifies with me in the Holy Spirit, that I have great sorrow and unceasing grief in my heart. For I could wish that I myself were accursed, separated from Christ for the sake of my brethren, my kinsmen according to the flesh, who are Israelites, to whom belongs the adoption as sons, and the glory and the covenants and the giving of the Law and the temple service and the promises, whose are the fathers, and from whom is the Christ according to the flesh, who is over all, God blessed forever. Amen.

This passage speaks of Paul’s broken heartedness over his own people’s (the Israelites) rejection of their Messiah. He has great sorrow and unceasing grief because they are not saved. However, Paul says that the adoption (along with other things) belongs to them. If adoption were something that occurred at the moment of conversion when a person puts their faith in Christ — as the major systems of theology affirm — how then could these unbelieving Israelites have received adoption? This problem is impossible to reconcile. This problem is particularly difficult for the Calvinist theological camp to answer, since they affirm that a person cannot lose their salvation. Therefore, someone to whom adoption belonged but who is unsaved is an irreconcilable problem.

However, if the adoption is a future hope at the redemption of our body (as Paul plainly indicates in preceding chapter of Romans), then Paul laments that these who initially received the promise failed to obtain it due to their lack of faith. It belongs to them in the sense that it was offered to them first (before the Gentiles), but it was not appropriated by faith. So, they have no hope of entering into this blessed truth, unless they repent and believe in the Messiah.

In fact, Paul still holds out hope and prays that his countrymen may repent and believe the gospel of Christ. He makes this clear in what he writes in the next two chapters of Romans.

Romans 10:1 (NASB)

Brethren, my heart’s desire and my prayer to God for them is for their salvation.Romans 11:23–24 (NASB)

And they also, if they do not continue in their unbelief, will be grafted in, for God is able to graft them in again. For if you were cut off from what is by nature a wild olive tree, and were grafted contrary to nature into a cultivated olive tree, how much more will these who are the natural branches be grafted into their own olive tree?

Romans 9–11 is an often debated section of Scripture. It is wise to read all three of these chapters together (really, best practice is to read the whole book of Romans in one sitting) when attempting to understand what Paul is discussing. Sadly, many pick and choose verses from these chapters selectively and do not interact with the entire teaching laid out from beginning to end, and thereby miss the actual intent of Paul’s teaching. The doctrine of adoption is merely one example.

Adoption in Galatians

Paul speaks of adoption again in Galatians 4.

Galatians 4:1–7 (NASB)

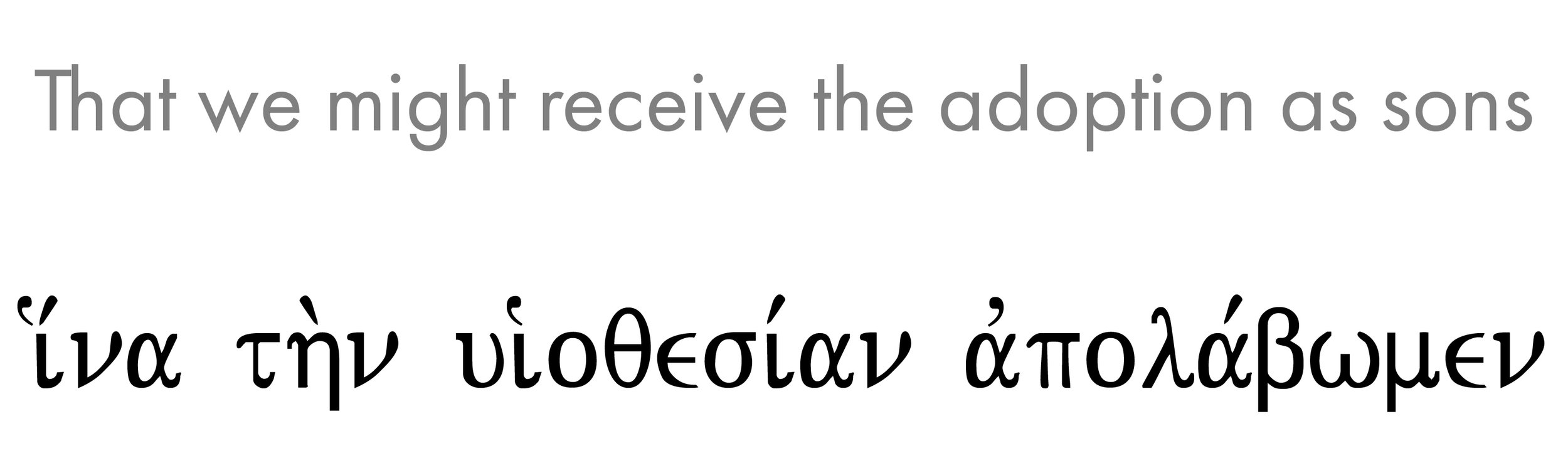

Now I say, as long as the heir is a child [GK: nepios], he does not differ at all from a slave although he is owner of everything, but he is under guardians and managers until the date set by the father. So also we, while we were children [GK: nepios], were held in bondage under the elemental things of the world. But when the fullness of the time came, God sent forth His Son [GK: huios], born of a woman, born under the Law, so that He might redeem those who were under the Law, that we might receive the adoption as sons [GK: huiothesia]. Because you are sons [GK: huios], God has sent forth the Spirit of His Son [GK: huios] into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!” Therefore you are no longer a slave, but a son [GK: huios]; and if a son [GK: huios], then an heir through God.

This passage articulates the same idea of our modern law. The “son” (heir) and the “slave” (non-heir) do not differ at all for a time, until the “son” comes of age. God the Father has sent His Son so that we “might receive the adoption as sons.”

Our assumptions are powerful when we read this passage. The phrase “that we might receive the adoption” is temporally ambiguous—that is, it could mean so that we might receive what we already received, or it could mean so that we might receive in the future.

Again, the already / not yet paradigm is set before us. We are sons by faith in Christ. This is why Jesus came when the fullness of the time came. The purpose of Jesus being born of a woman, born under the Law is given in two clauses:

So that He might redeem those who were under the Law;

So that we might receive the adoption as sons.

The grammar of both clauses is very similar. For views that hold redemption and adoption occur virtually simultaneously at the moment of conversion, these clauses are essentially repetitive. However, if we take Paul’s comments from Romans about adoption being yet future at the redemption of our body, then we see both the already / not yet aspect of salvation in view. Instead of repeating himself, Paul is affirming the beginning of salvation (redemption) and the end of salvation (adoption) in these clauses.

Paul urges them to walk in freedom as children of God, not submitting themselves to spiritual bondage again. Paul urges them to continue on this path “until Christ is formed in” them (Galatians 4:19).

A Brief Grammatical Excurses

Grammar is not everyone’s favorite part of Bible study. That’s understandable. It is important to note here a grammatical feature of this passage, simply because many have twisted and abused this text with superficial analysis.

The NASB phrase, “that we might receive the adoption as sons” is eight English words. This is the translation of just four Greek words. This is a very accurate translation. The additional English words are all necessary to understanding what these four Greek words are communicating.

The first part of the clause — “that” — is a direct translation of the Greek coordinating conjunction. This is a common and straight-forward translation. Other possibilities are “in order that” or “so that.”

The final part of the clause — “the adoption as sons” — is a direct translation of the Greek. The translation could simply be “the adoption” (cf. NAB). Other modern translations attempt even more explanation: “that we may be adopted with full rights” (NET) or “that we might receive the full rights of sons” (NIV).

The most exegetically significant portion of this clause is the verb. It’s most significant because this is the place where errors, if any, will be made. This is a first plural subjunctive aorist active verb. Each of these terms is meaningful. We’ll briefly discuss each.

Since it is first plural, this is where the “we” comes from. The “we” is the subject of the verb. This is an active verb, which tells us how the subject relates to the action of the verb. In this case, it seems clear that “we” are the ones doing the “receiving.” This verb is also in the subjunctive mood, which is best understood as putting the action of the verb within the realm of potentiality (as opposed to actuality). The force of this mood expresses that this is the intention, that “we receive the adoption.”

Each of those elements is relatively free from controversy grammatically. It is the final element that may cause some to make an error in their exegesis.

The verb is also aorist. Even if you’ve never studied Greek, if you’ve listened to a lot of sermons, you’ve probably heard a preacher or teacher talk about the aorist. It is often oversimplified and described something along the lines as being, “about a once-for-all action completed fully and completely in the past.” While there are certainly cases where this definition is perfectly accurate, it does not reflect the full range of the aorist in Greek. In fact, a leading Greek scholar who wrote the book Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics tells us that “tense is used primarily to portray the kind of action” (Wallace, 443).

The superficial (but widely circulated definition) touches on the kind of action: once-for-all. The grammatical term is punctiliar, as in a point in time. However, the superficial definition also includes past time. In English, we are much more accustomed to hearing tense associated with time: whether, past, present, or future. However, Wallace continues: “outside the indicative and participle, time is not a feature of the aorist” (Wallace, 555). In our present passage, our verb is neither in the indicative nor a participle. Therefore, the aorist is not telling us when at all! It’s only telling us the kind of action, not the time of the action.

This passage is speaking of adoption as a once-for-all type of event. It is not envisioning the process but the action as a whole. However, some may incorrectly assert that this adoption was past (that is, Paul is telling these Galatians they were adopted back when they were converted) because of the aorist. If this were an aorist indicative rather than an aorist subjunctive, that would be true. In that case, the translation would be something like, “so that we received the adoption.” Instead, Paul uses the aorist subjunctive. It seems he is reminding the Galatians of the purpose of Christ’s work and encouraging them to continue in the truth so that they might receive the adoption in the future.

This interpretation fits better with the grammar than a past event does. It also fits perfectly well with Paul’s statements concerning adoption in Romans 8 and 9. Paul doesn’t want these Galatian believers to be like his unbelieving countrymen, to whom belonged the adoption, yet who rejected the Messiah and continued in unbelief.

Read the whole book of Galatians again with this perspective. Examine to see if this fits with the overall context of the whole book.

Adoption in Ephesians

A final passage must be examined from Paul regarding adoption. We read it in Ephesians 1.

Ephesians 1:3–14 (NASB)

Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places in Christ, just as He chose us in Him before the foundation of the world, that we would be holy and blameless before Him. In love He predestined us to adoption as sons through Jesus Christ to Himself, according to the kind intention of His will, to the praise of the glory of His grace, which He freely bestowed on us in the Beloved. In Him we have redemption through His blood, the forgiveness of our trespasses, according to the riches of His grace which He lavished on us. In all wisdom and insight He made known to us the mystery of His will, according to His kind intention which He purposed in Him with a view to an administration suitable to the fullness of the times, that is, the summing up of all things in Christ, things in the heavens and things on the earth. In Him also we have obtained an inheritance, having been predestined according to His purpose who works all things after the counsel of His will, to the end that we who were the first to hope in Christ would be to the praise of His glory. In Him, you also, after listening to the message of truth, the gospel of your salvation—having also believed, you were sealed in Him with the Holy Spirit of promise, who is given as a pledge of our inheritance, with a view to the redemption of God’s own possession, to the praise of His glory.

While there is much to unpack in this amazing passage, we will limit ourselves to discussion of the theme of adoption. Once again, we see the already / not yet dichotomy in play.

If the traditional view regarding the doctrine of adoption is correct — namely, that this happens virtually instantaneously at the moment of conversion — then this is a curious statement indeed. Let’s again review the traditional ordo salutis options:

If the Calvinist, Amyraldian, or Arminian/Wesleyan schemes are correct, the Apostle Paul picks the eighth event in the list to say God predestined us to. That is, Paul does not say God predestined us to election, calling, regeneration, faith, repentance, or justification. Neither does Paul choose to say God predestined us to sanctification, perseverance, or glorification. Why choose such an odd place in the ordo salutis to declare God’s decree of predestination?

As this passage continues, Paul states explicitly what we have and what we look forward to.

We have redemption through His blood, the forgiveness of our trespasses.

We have obtained an inheritance.

We have been sealed with the Holy Spirit of promise, who is a pledge of our inheritance.

This pledge is the guarantee of our future entrance into that inheritance, which we look forward to (or have a view to).

The term “pledge” (variously translated as seal, down payment, earnest, first installment, or guarantee) is the Greek word arrabon. It appears only three times in Scripture, always by Paul, and always speaking of the down payment of the Holy Spirit given to the redeemed by God (Ephesians 1:14; 2 Corinthians 1:22 and 5:5). This pledge is an initial deposit which gives us confident hope of the future, full inheritance.

Paul makes it clear: the inheritance is something we receive after we have finished our work on earth. It is a future reward.

Colossians 3:22–25 (NASB)

Slaves, in all things obey those who are your masters on earth, not with external service, as those who merely please men, but with sincerity of heart, fearing the Lord. Whatever you do, do your work heartily, as for the Lord rather than for men, knowing that from the Lord you will receive [future] the reward of the inheritance. It is the Lord Christ whom you serve. For he who does wrong will receive the consequences of the wrong which he has done, and that without partiality.

The Apostle Peter agrees. He points the faithful follower of Christ to the future inheritance, reserved for us in Heaven.

1 Peter 1:3–9 (NASB)

Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who according to His great mercy has caused us to be born again to a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead, to obtain an inheritance which is imperishable and undefiled and will not fade away, reserved in heaven for you, who are protected by the power of God through faith for a salvation ready to be revealed in the last time. In this you greatly rejoice, even though now for a little while, if necessary, you have been distressed by various trials, so that the proof of your faith, being more precious than gold which is perishable, even though tested by fire, may be found to result in praise and glory and honor at the revelation of Jesus Christ; and though you have not seen Him, you love Him, and though you do not see Him now, but believe in Him, you greatly rejoice with joy inexpressible and full of glory, obtaining as the outcome of your faith the salvation of your souls.

The best understanding of what Paul is expressing about adoption in Ephesians 1 is that the glory of what God has done in Christ looks to the end — the “destination” — of our faith in Christ. This destination is the same for all believers: we will one day be conformed to the image and likeness of Christ. All of this will be accomplished by grace. It will be done to the praise of His glorious grace (Ephesians 1:6, 12).

This is essentially what Paul said in Romans, “For those whom He foreknew, He also predestined to become conformed to the image of His Son, so that He would be the firstborn among many brethren” (Romans 8:29). The destination for all believers — the end — is conformity to Christ.

Concluding Thoughts on Adoption

The doctrine of adoption should be a great cause for hope and celebration. It is something for which Christians eagerly long for. If we are born-again, we have the pledge of this future inheritance in the indwelling Holy Spirit, who serves as a seal of our future inheritance in the coming kingdom of Christ.

Sadly, this doctrine has largely been misunderstood. This has created myriad opportunities for Christians to fight over whether or not God predestines certain individuals to faith. Of course, the Bible nowhere declares that God predestines anyone to believe. By incorrectly defining adoption as an event at or around the moment of conversion, this argument persists because we have mistakenly conflated the terms of faith / repentance / justification / adoption to be virtually synonymous in their meaning and timing.

Despite the popularity of these theological schemes, understanding adoption as the end of our salvation process in agreement with Paul’s eager expectation and hope, we are able to see more clearly what God has revealed. All Christians, who have put their faith in Christ — no matter where they begin — are predestined to be conformed to the image and likeness of Christ, to the praise of His glorious grace.

If you are a Christian, you should be walking a path of sanctification that is leading you more and more to be like Christ over time. To the praise of His great name.

Related Question

What is the spirit of adoption? The Spirit of adoption, referred to in Romans 8:15, is the indwelling Holy Spirit that enables Christians to cry out to God as our Abba Father. The Holy Spirit is the spirit of adoption who both leads God’s children (Romans 8:14) and bears witness with our spirit that we are children of God (Romans 8:16).